Seventy-two dots per inch

- 4 min read

In many classrooms, teachers explain to schoolchildren that a line is a geometric shape with only one dimension. In the Imperial System of Measurement, however, a line is a unit of measure equal to one poppyseed. Four poppyseeds, or lines, equals one barleycorn. Comical as it may sound, this is the world of length measurements below one inch, and, believe it or not, they impact the work we do and the technology we use.

The Imperial System is not random. Each measurement is derived from something or creates something. There are twelve inches in a foot, three feet in a yard, two yards in a fathom, one hundred fathoms in a cable, and ten cables in a nautical mile. There are two inches in a stick, two sticks in a hand, and three hands in a foot. A mile is eight furlongs. In each case, there was a purposeful intention of measurement that meant something to those who created it. Cables and nautical miles are useful to seafarers, hands are useful to equestrians, and many of us know of 72 dots per inch (DPI), which is useful to technologists.

To understand the origin of 72 DPI is to understand length measurements smaller than an inch. We've already seen that three barleycorns constitute an inch. This measurement, of course, is by convention. An inch is not some random length based on the size of some king's thumb. It's three barleycorns, a unit of measure still used for calculating shoe sizes.

While several measurements of length in the Imperial System are named for parts of the human body, such as a finger, which is seven-eighths of an inch (imagine the king with an inch long thumb and 7/8" fingers), others are taken from things in nature, such as barleycorn and poppyseed. Still others from standard sizes of manufactured items, such as nail or rope.

If we go far enough through history and small enough in measure, we get to the point. There are six points in a line (or poppyseed), four lines in a barleycorn, and three barleycorns in an inch. If you do the math, that's 72 points in an inch.

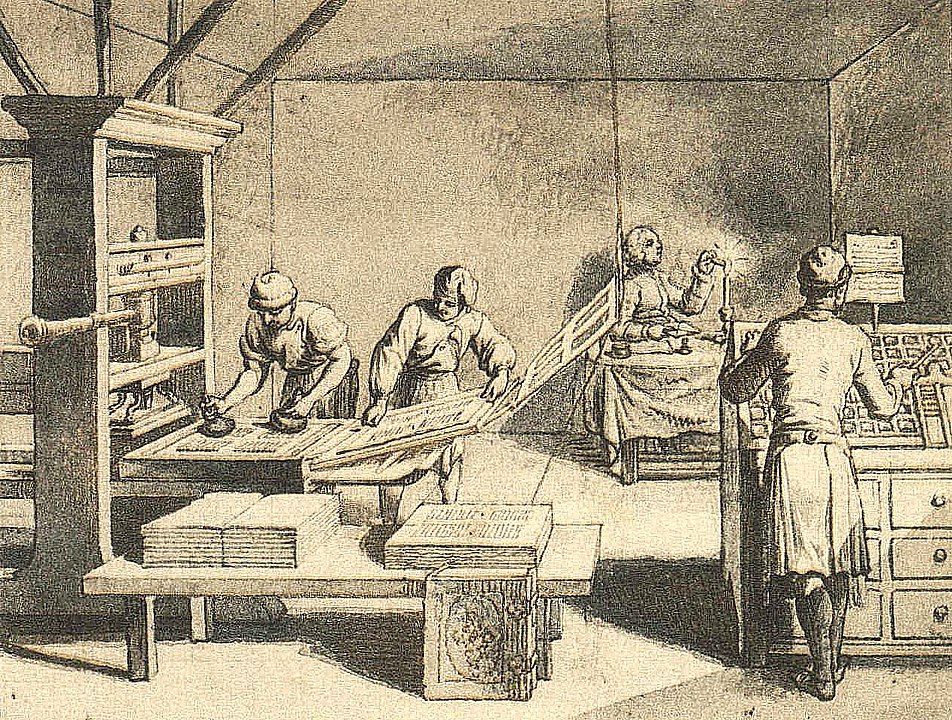

The point is a vital measurement unit in printing and extends back to the early days of typesetting, revealing how some units of the Imperial System were possibly defined. Early typesetters sought a standard small enough to measure letter sizes, spacing, leading, etc., and settled on the point. Of course, as I'm sure you can imagine, the actual size of that measurement varies by country, as it seems with all Imperial units. Every nation that uses, or has used, the Imperial System defines it differantly, so a point is one thing in France, another in Italy, and, well, this is why everyone chose metric instead. In the United States, however, we soldier on, and by US measurements, there are 72 points to an inch.

For years presses around the globe churned out endless pages, typesetters happily understanding the scale of measurement in their isolated worlds. A typeface of 72 points in the US will take up one inch of vertical print space. Except when it doesn't, like, when it's on a computer screen. Friends and neighbors, say hello to MacIntosh.

The 1980s were a time of turmoil, innovation, and change. For the first time, computers entered the workforce in large numbers, free of the constraints of massive mainframes, and placed before droves of office workers. The MacIntosh was revolutionary for many reasons, including the introduction of digital wonder to the world of publishing. For the first time, a typesetter could see on the screen exactly what would be on paper, and programs like QuarkXPress replaced drawers full of little lead blocks of letters. For a system, like the MacIntosh, with a screen built into the computer, sizing the onscreen type became a choice of how many pixels constituted an inch of screen space. Seventy-two, of course.

Except, no. Seventy-two pixels on a screen is ever so slightly less than an inch. It worked as a standard for the screens at the time, most resolutions being equal, but it was still less than an inch, and mistakes were inevitable. As a standard, however, it worked because nothing would change for the time being. Up the coast from where the Mac was created, in a place called Redmond, some software engineers examined the problem of how many pixels are actually in an inch of screen space and chose a subtle, if problematic, solution. They would cheat.

Microsoft sought a way for an inch of type to be an inch of type on both paper and screen and added 24 pixels. In those days, computer screens were mainly the same when it came to resolution, which, generalizing, provided 96 pixels in a screen inch. So Microsoft engineers scaled everything up. This was the standard for seeming ages, Mac at 72 DPI, and Windows at 96. Wait, DPI? Weren't we talking about pixels?

In all of this screen wizardry, someone looked across the room and noticed the printer. Shit. OK, "dots" comes from the dots of ink an inkjet printer places on a page. Seventy-two dots to an inch, right? Yep. Like the 72 points in an inch of moveable type, there were 72 dots in an inch of digital type and 72 pixels in an inch of Mac screen space, even if the inch on the screen was smaller than the inch on the paper. Imagine the emerging complexities and problems of 96 pixels in an inch.

In all fairness, Microsoft needed a solution for any and all screens and any and all printers. However, their world was not as controlled as Apple's, and they had choices to make. Even if those choices made sense at the time, history has not been kind. Despite that, it doesn't matter anymore. Screen resolutions are denser and more diverse than ever, the print influence is now irrelevant and overcome, and technology exists in its own ecosystem. Yet, in the US Imperial System, 72 points is still an inch.

Seventy-two and 96 DPI are relics in a world that determines and adapts its standards free of the legacy and internationally non-standard typesetting rules. However, screens are still measured in DPI, still derived from the Imperial System that gave us the point, the unit once created by those who needed a way to measure small distances using natural means. Complicated, diverse, and confusing as it may be, the Imperial System of Measurement is remarkable. Whether we realize it or not, things long forgotten still significantly impact modern measurement and lexicon. Even the way we determine measurements now is not far from the regional definitions of what a particular unit means, whether an inch on a page or an inch on a screen. By the way, there are 12 points in a pica and six pica in an inch. For those who measure type in pica instead of points. Probably.