The calories in cocktails

- 9 min read

How often do you think about calories when pouring a cocktail? Likely not often enough, especially if you’re already counting calories in food, or tracking your macros. This isn’t unusual as we don’t often consider the cocktail as a source of calories, at least not enough to make an impact, but you may be surprised to find that they do, can, and will affect your nutrition. This isn’t a dire warning, of course, but a little mindfulness can go a long way when considering alcohol consumption, and accounting for it as part of a nutrition or fitness plan.

What are calories?

Obviously, we’re not talking about those special occasions where you indulge, or perhaps over-indulge. Those times, as long as they’re not every day, are healthy, and everyone should have a moment, either with or without alcohol, to enjoy whatever requires celebrating, such as the end of finals, that new promotion, or a dear friend’s engagement. However, those days are not every day, and, if you enjoy a drink at happy hour, or a nightcap as part of your routine, it’s certainly advantageous to understand something about the impact those drinks have on your nutrition.

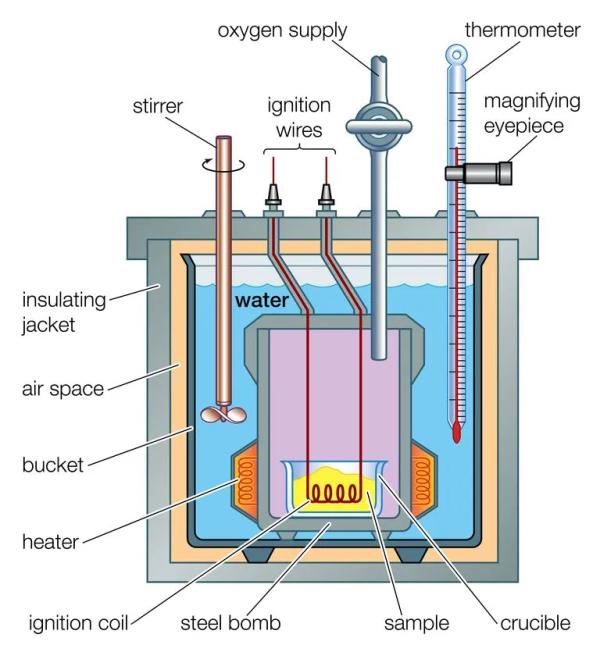

Bomb calorimeter

Bomb calorimeter

Does alcohol have calories? Yes it does, but to understand what it means to consume calories in cocktails, let’s first understand what is a calorie. Simply stated, a calorie is the amount of energy it takes to increase the temperature of one gram of water by one degree Celsius at standard atmospheric pressure. Calories are measured by placing an item in a contraption called a “bomb calorimeter,” a metal cup that sits in a small pool of water. The item is then oxidized, and the resulting effect on the temperature of the surrounding water will indicate the number of calories. Calories themselves are very small units of measure, and the numbers we use, and that are printed on packages at the grocery store, are in kilocalories, or Calories. A Calorie (with a capital “C”) is 1000 calories, as is a kilocalorie, which means you may see calories written as 200 Calories, 200 Cal, 200 C, or 200 kcal, all of which are synonymous.

The bomb calorimeter test, although effective, is no longer used when determining calories in food. In 1990, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rewrote the rules of food labels, it also allowed for an aggregate system of measure, called the Atwater system, which calculates calories based on the nutrients in the energy providing components of the food. The Atwater system is more cost effective, but, in some ways, less accurate because the results may or may not include non-digestible components of food, such as fiber, in the calorie count.

What are macros?

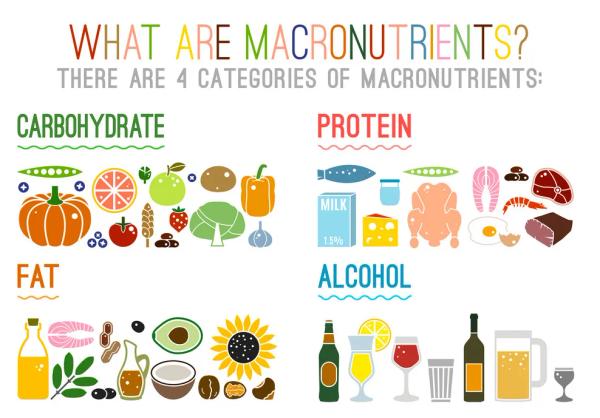

The Atwater system works by using math to add up the total calories in the nutritional components of food. These components are called macronutrients, or macros for short. There are four categories of macros: carbohydrates (carbs), fats, protein and alcohol. On a food label you’ll see total calories, and a breakdown of those calories by macros, which have standard measurements. Within each macro category there may be different kinds of fats or proteins, etc, but each category has the same amount of calories per gram, and break down like this:

- 1 gram of carbs has 4 Calories

- 1 gram of fat has 9 Calories

- 1 gram of protein has 4 Calories

- 1 gram of alcohol has 7 Calories

Using these values, a producer can measure, in grams, the different macros a product contains and calculate the total calories. Let’s consider a food item that has 11 grams of fat, 26 grams of carbs, and 3 grams of protein in a single serving. If we do the math, that means it has 213 Calories. Of course the total calories you get might not match the label because labels give values in whole numbers, not decimals, but, overall, if you are close to the label, the label is mostly fairly accurate.

It’s an effective system for standardizing both the measurement and presentation of nutritional information, and for tracking nutrition and fitness. In fact, we’ve become used to it, and are all, in one way or another, familiar with both calories and macros. Except, that is, for alcohol.

Alcohol is a macro

There’s no alcohol in food, so why put it on the label? You can find nutritional information on a can of soda pop, but not on a bottle of beer. Some alcoholic beverage producers have started putting nutritional information on their containers, but they are in the minority. The FDA does not require nutritional labels on alcoholic beverages, so we’re left wondering where does the alcohol macro fit in a nutrition plan? The answer is that it fits the same way as the other 3 macros, but we don’t often track it among them. However, that doesn’t mean there is no impact, or that they can be hidden in other metrics. Alcohol is a macro, and we have to deal with it.

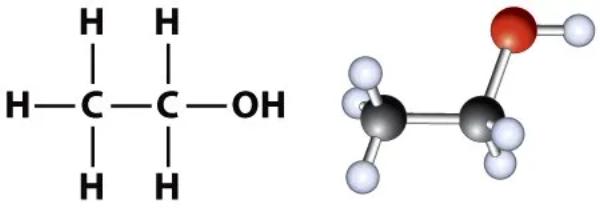

Unlike carbs, fat, or protein, alcohol depends on just how alcoholic it is. The 7 calories per 1 gram of alcohol applies to 1 gram of pure alcohol, so for us to figure out the calories we get from alcohol in a beverage, we must know how much of that beverage is alcohol by volume (ABV). If we have an ounce of vodka, and we know the vodka is 40% ABV, we can calculate the calories in the alcohol by first calculating the mass of the vodka. You can calculate the mass of the vodka using this formula, knowing that the density of alcohol is 0.79 grams per milliliter, and the density of water, the remaining part of the vodka disregarding any flavoring agents, is 1 gram per milliliter:

x = milliliters of 40% ABV vodka

y = mass

0.6x + 0.4(0.79x) = y grams

Breaking it down, 0.6x is the 60% water, and 0.4(0.79x) is the 40% alcohol. Working through the problem, we first convert to metric, 1 fluid ounce of vodka is also 30 milliliters of vodka, then apply the formula and know that we have 18 grams of water, and 9.5 grams of alcohol. If we then take the mass of the alcohol, 9.5 grams, and multiply by 7 we find that one ounce of 40% ABV vodka has 66 Calories, at least for the 40% that is alcohol, not the other 60% of water and stuff in the drink.

The calories of components

One can open a web browser and search for calories in cocktails and find any number of pages and sites that list a variety of drinks, and the calories in them. If you do this, select about six or so and compare them, finding, even if they have some of the same cocktails, their numbers differ greatly. Sure, they’re likely accurate, but you need the recipe and ingredient list, at least, to verify them. A better resource comes from the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (NIH) who’ve created an online calorie tool for alcoholic beverages. It’s a little more helpful, but still leaves alot of guesswork, especially when it comes to cocktails.

Remember that calculation we did to find the calories in an ounce of vodka? We came up with 66 Calories, but the NIH tool indicates 97 Calories for 1 1/2 ounces of 40% ABV vodka. Close enough. We come up with 96 when using our calculations, but the 1 Calorie difference accounts for latitude in our conversion (1 ounce isn’t exactly 30 milliliters), and rounding the results to whole numbers (the real result you get with the above formula, which you also got if you’re working along, is 66.36, which, adding half and rounding for the ounce and a half used by the NIH, is 97).

While the NIH data may get us closer, it’s still no good. One cannot say that every 40% ABV gin has the same number of calories, just as one cannot say that the calorie count in one brand of 40% ABV gin is the same as every 40% ABV whiskey, and so forth. We can only say those values are true for the 40% that is alcohol. A more granular measurement is needed. For spirits, we must assess calories based not only on the percentage of alcohol, but on the other ingredients and additives.

Consider rum. According to NIH, all 40% ABV rum, just like all 40% ABV gin, and all 40% ABV whiskey, etc. is 97 Calories. Fair enough for the alcohol, but what about anything else added to the rum, such as sugar? One has to know how much sugar is in the rum, and, while the practice of adding sugar to rum is accepted, not all producers do it, and those that do add different quantities by mass. That’s not something we can figure out simply with a calculator, we’d have to find a way to measure the sugar. Sure, the sugar in a beverage can be measured, but in a world of natural sugars, i.e. the ones already in the liquor, and the possibility of added sugar, and maybe other things, that 97 Calories really only works for the cleanest sample of vodka.

Aging adds other characteristics, and ingredients, even if in trace amounts and not all of which will contribute calories. If that’s not enough, we wander into a dark forest indeed when we consider other things, like liqueur, and non-alcoholic ingredients. If you’re using fruit juice, or syrups that you made and know are just sugar and water, you can find the calories pretty easily, but not so with liqueur. They can be calorie bombs if they’re sweet enough, or creamy enough such as with Irish cream, but you’ll never know exactly what, and how much because there is no nutritional information, or ingredient lists on alcoholic beverages.

Alcohol and the body

The human body considers alcohol as a poison, and will eliminate it from the system as quickly as possible. The more alcohol you ingest, and the faster you ingest it, the more difficult it is for the body to expel it. We’ve already seen how murky it can be when calculating the calories in an alcoholic beverage, but it gets worse as you account for percentage ingested over time.

Photo by Yoab Anderson on Unsplash

Photo by Yoab Anderson on Unsplash

Since the body disposes the alcohol, you might not get the same amount of calories you calculated. If you drink less alcohol, and/or drink slower, the body deals with it more efficiently, and some calories flow away with the waste, but drink too much too quickly, and your body can’t handle it. In that case you might get drunk, but you’ll also make full use of the calories on offer. Of course, this only applies to the alcohol, so don’t count on pouring a Pina Colada short and hoping to lose weight. At almost 500 Calories, with nearly 400 of them from the Coco Lopez and pineapple, you’re still, for all intent and purpose, consuming a small meal.

Also consider metabolic rate, and how well the body digests things in the first place. We already know the Atwater system of calculating calories in food is not as efficient as the bomb calorimeter, but that’s totally OK, because all we can hope for, in the end, is a ballpark figure. Accurate figures require knowing not only how many calories are in a food item, but how well a given consumer of that item can access those calories. This, in a sense, is effective calories, and every person is different, so, no matter how accurate the label is, or how carefully you measured and calculated the calories in your drink, it’s still just an informed guess when applied to each one of us individually.

Putting it all together

Saying this, that, or the other cocktail has X Calories in it is a fool’s errand. Every bar pours differently, spirits are not all the same, ABV numbers are never nice, round, and tidy, the ingredients are unknown, and quantities, except when you poured it, are only assumed. We’re much better off dealing with the component ingredients, then adding it all up. Looking up the calories in fresh juice is easy enough, and bottled juice will have information on the label, but spirits won’t, so we need a way to make reasonable estimates.

The best way to do this is by making everything yourself. No, we don’t mean distill your own gin, but we do mean squeeze your own juice, make your own syrups, and buy what you can’t make from reputable producers. You don’t have to, but if you make that Gimlet with homemade lime cordial, not only did you use real sugar and fresh lime, but you know how much of each you used, and, therefore, how many calories. On the other hand, if you’re using Rose’s Lime Juice you’re ingesting mostly high fructose corn syrup, and we’ve all had enough of that. If you like Rose’s, go for it, but, if you’re concerned about what you’re putting in your body, both in terms of calories and quality ingredients, make your own.

As for spirits, buy local. If you care about the consumables you ingest, you’re likely not going bottom shelf at the liquor store, and, even if you do, you can still shop intelligently. But, while you may spend more on better quality spirits, you can still only estimate what’s in them. Buying local is your best bet for more accurate estimates, because, in most cases, if you are diligent and polite, you can go to a tasting room, talk to the people who made the liquor and get a sense of how they treat it, what they put in it, and the quality of the materials from which the spirit was made.

In the end, until the FDA mandates nutritional labels on alcoholic beverages, we’ll never really know. We can, however, follow one simple rule of thumb: save the cocktails with lots of cream and/or sweeteners, like the Pina Colada, for special occasions, not every day, and treat the rest as candy. When you stop for a drink after work, and thoroughly enjoy the Cosmopolitan you ordered, consider it in the same way you would a Snickers bar. If you would eat a second Snickers bar, go ahead, have another Cosmo, but remember, in either case, both choices often precede a meal, both choices contribute calories, and all calories matter, especially the ones from things, like booze and candy, that don’t fill you up, the so called empty calories. So next time you’re tracking macros, don’t forget the alcohol, then drink healthy and local, just like you eat.