The UX of beverage recipes

- 12 min read

Recipes are ubiquitous. It’s likely everyone, at some point in their lives, will use a recipe, maybe for food, maybe for drinks, or maybe for craft items. The format is simple enough. At its most basic it’s a title, a description with a picture or two, a list of ingredients, and instructions. Some might add servings, prep time, or nutrition info, but it’s still a recipe, something that should be easy to use because you’re likely using it while doing stuff. So why are some recipes easy to follow and use, while others aren’t?

We spent alot of time thinking about how best to present and use recipes. At The Portland Pour, recipes are some of our most common content, and we wanted a format that would be easy to use, whether you’re at a desktop, on your phone in the kitchen, or in print on a recipe card, and we came to some conclusions about what makes a recipe work for, in our case, beverages.

Our research included a very unscientific survey of recipes around the web. We took a random sampling of about 2 dozen food and beverage recipe sites, from Epicurious to Bon Appetite, to random food blogs. We took a look at other sites like Punch, Imbibe, Difford’s Guide, and random cocktail and soda blogs. We surveyed anything we could find on recipe style, publishing guidelines, or digital formats. Finally, we got into the old books like the Joy of Cooking from 1950 something, cocktail guides from the 1930s and older, and newspaper and magazine archives at the library because who doesn’t love a micro-fiche machine? The results were all over the board, and the older the sample, the more confusing it often was. There’s also alot that works, and we’re both encouraged and inspired by some of our samples.

A note on measurement units. We use imperial measurements for our own recipes, and, as noted later, were not satisfied with the conversions to metric. We tried listing recipes as both imperial and metric, but the conversions always had problems in the details. As a local, US based project, most of our work will use imperial measurements, however, we do not convert metric recipes. Instead, we publish the recipes as written, which is almost always imperial, with the occasional metric.

Pain points

Recipes can add friction in several ways, from how ingredients are listed to how instructions are written. The latter turned out to be the biggest problem. Too often instructions were unnecessarily verbose, skipped important information, or, strangely enough, too well written. Yes, active voice is always preferable, as are proper declarative sentences, yet it turns out that short simple steps are exactly what a recipe needs.

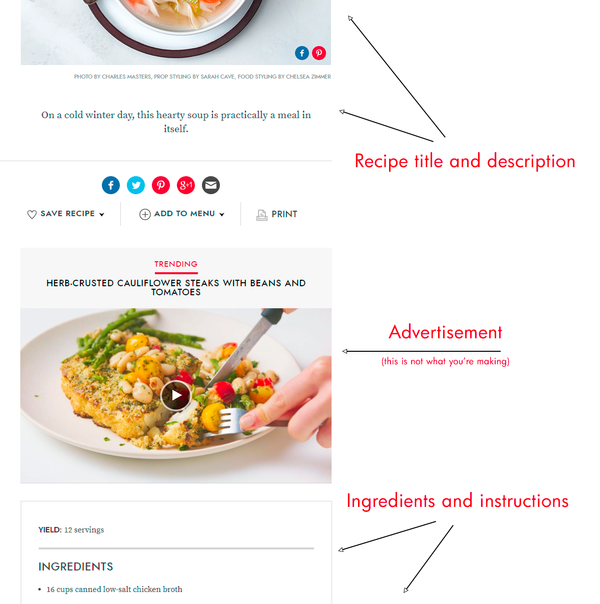

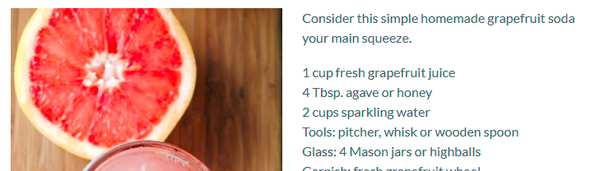

Another problem is positioning. The instructions should be near the ingredients, which should be near the title and any pictures. This was not the case in all of our samples, some being separated by advertisements, others placed horizontally on the page. Vertical alignment seems easiest to use, and that counts for ingredients, too. Some samples listed ingredients in a single line, separated by commas, others placed them too close to each other, and others used numbered lists.

We then consulted our own writing style guide, The Associated Press Stylebook, which we use for all of our written content, and which also provides guidelines for formatting recipes. We like the AP style for almost everything, except their recipe guidelines, but they are all quite reasonable, and began as our starting point.

Measurements

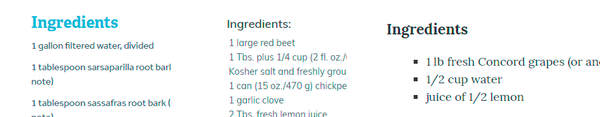

Ingredients are useless without measurements, and our samples all had different ways of noting quantities. Some used abbreviations, some didn’t. Some spelled things out completely, some didn’t. Some used decimals, others used fractions.

The AP style calls for fully spelling measurement units in lower case and many websites we found follow this advice. In fact, we noticed a trend toward fully spelling out units of measurement.

- 1 cup

- 3 teaspoons

- 1 tablespoon

- 15 milliliters

- 200 grams

In the interests of space, and keeping our layout consistent across devices, we chose to use standard abbreviations instead. Drink recipes deal with fluid ounces, teaspoons, dashes, and item quantities (such as 1 cherry). There’s no accepted abbreviation for a dash of something, so we spell that out, along with any measurement that isn’t ounces, teaspoons, or tablespoons, and item quantities are numbered unless the item is usually only included one at a time. Finally, there are no plural abbreviations (always “oz” never “ozs”). Metric is another matter, and much easier. If we have metric units, it’s all milliliters and dashes, the former abbreviated as ml, and the latter spelled out.

- 2 oz

- 1 tsp

- 2 dashes

- 30 ml

- 3 cups

- 1 pint

- 2 olives

- A lemon peel

In our samples, units used varied. Most cocktail recipes we found list measurements in ounces, milliliters, or centiliters (oz, ml, cl, respectively), and most soft drink recipes, both from beverage and food sources, use cups, or liters. We found it mattered only when there was no standard pattern. For us, we use ounces and milliliters.

It’s also important not to mix units of measure. Imperial measurements can be tablespoons, ounces, cups, pints, etc. It got confusing when mixing them together, just as it is when mixing ml and cl in the same ingredient list.

All measurements should use similar units where possible. Again, for metric, not a problem, but for imperial measurements there are some choices to make. For instance, 1/2 Tbsp is the same as 1/4 oz, and ounces is a common beverage unit of measure, so specify all ingredients in ounces until too small to measure in ounces. At that point you’re in dash or teaspoon territory, so rule of thumb should be, if it’s less than 1/4 oz, and more than a dash, it’s a teaspoon.

Yes:

3/4 oz Lime juice

1/4 oz Simple syrup

No:

3/4 oz Lime juice

1/2 Tbsp Simple syrup

Where partial quantities are needed, fractions are preferred. Again, metric isn’t a worry because it doesn’t use partial units. It’s almost always a nice round number, like 30 ml, or 200 grams. As a side note, we use both metric and imperial units, just not at the same time. We tried converting recipes from one to the other, and it never really worked as well as we’d hoped, so now we just keep the recipes in the units in which they were created. For us, that’s mostly imperial, and, as a local project with an audience mostly in the US, we will, by consequence, favor imperial measurements.

- Yes: 1 1/2 oz

- No: 1.5 oz

In the case of 2 numbers adjacent to each other, we stick with the AP guidelines, and spell out the first number.

- one 12 oz can of Pepsi

Where there may be confusion on the proper unit of measure, such as a dry product measured in ounces (fluid measure or weight?) we spell all measurements fully throughout.

- 1 fluid ounce Citric acid

- 1 fluid ounce Water

- 1 teaspoon Lemon juice

Ingredients

Ingredients themselves have 2 concerns: how do you, or do you capitalize them, and how do you delineate them, both from their measurements, and from each other.

In almost all of our samples, ingredients aren’t capitalized unless they are brand names or other proper nouns, such as London dry gin. This is also as specified in the AP guidebook, however, neither our samples, nor the AP delineate the ingredients from their measurements, and this made things a little difficult to read at a glance, especially if working from a handheld device. We chose to sentence case ingredients as a way to use the capital letter of the ingredient to delineate it from the measurement. This is most useful during prep, especially for those who use two glances for every ingredient, one glance for the measurement so the proper measuring tool can be selected, and one glance for the ingredient itself.

- 1 oz Lemon juice

- 1/2 oz Pineapple gomme syrup

- 1/2 oz Grenadine

- 2 cups Brewed coffee

- 1 1/2 oz Old tom gin

Brand names are always capitalized and spelled out in full.

- 4 oz Royal Crown Cola

- 2 oz Bull Run Single Malt Whiskey

- 1 1/2 oz Ransom Old Tom Gin

Capital letters help delineate ingredient names from their measurements, but what about from each other? Some of our samples use bullet lists, others use relaxed line spacing, others use numbered lists and still others use single line spacing. The AP recommends single line spacing, but that’s hard to read, as are numbered lists. The list numbering sometimes gets confused with the unit of measurement, so we went with both bullet lists and relaxed spacing. We use bullet lists on some of our newer online recipes, and add line spacing on our print recipes. Using bullets takes up space, but there doesn’t seem to be a usability impact with bullet lists.

Ingredient order

This seems like it would be easier than it is, but the order of ingredients matters. In cooking, ingredients are often listed in the order in which they are used, but in most beverage recipes, that’s not much of a concern. Often a cocktail recipe is a list of ingredients that all get mixed up at once. Sure, if the order in which ingredients are used matters, such as “in a mixing glass muddle the mint,” then those ingredients do come first, but, for the rest? It comes down to preference. Some like to list ingredients by type, i.e. base spirit, then any liqueurs, then any juice, then any sweeteners, and finally any finishing items such as bitters. Others, including The Portland Pour, like to list ingredients by descending quantity, 2 oz of this, then 1 oz of that, then 1/2 oz of the other thing. In cases where quantities are similar, we place the ingredient most often used in quantities greater than the other one(s) first.

- 1/2 oz Lemon juice

- 1/2 oz Simple syrup

The exception to the descending quantities rule is base spirit. If there’s more juice than vodka, such as in a Harvey Wallbanger, the base spirit comes first, then all the rest of the ingredients in descending quantity. This makes it easier to glance at the ingredients and know what type of drink it is. Is it a vodka drink, or a whiskey drink, or a soft drink, etc.

- 1 oz Vodka

- 4 oz Orange juice

- 1/2 oz Galliano L’autentico

If there is an ingredient that must be used before the others, it comes first, before the base spirit, such as in a Southside, which requires the maker to first muddle some mint.

- 4–5 Mint leaves

- 2 oz Aria Gin

- 3/4 oz Lemon juice

- 1/2 oz Simple syrup

If there are many similar quantities, such as in an equal parts cocktail, or others with lots of the same measures, we follow the base spirit, liqueur, mixers, modifiers, finishers pattern. Here’s an example of a recipe, Fish House Punch, with lots of similar quantities. Notice how there are 2 base spirits, rum and brandy, each the same amount, so, alphabetical order is used for them, then comes a liqueur, and lemon juice, then the rest.

- 3/4 oz First City Rum

- 3/4 oz Treos Brandy

- 3/4 oz Giffard Crème de Pêche de vigne

- 3/4 oz Lemon juice

- 1/4 oz Cane sugar syrup

Topping and finishing items always come at the end of the list, because they’ll be used last, but they might not always have a quantity, such as in a recipe for a French 75, which calls for mixing the first three ingredients, then topping with sparkling wine, how much of which you use depends on the size of the glass in which the drink is served.

- 1 1/2 oz Aria Gin

- 3/4 oz Lemon juice

- 1/4 oz Simple syrup

- Sparkling wine

What about garnish? Most cocktails involve a garnish, which may, or may not be included on the ingredient list. Often times garnish is a suggested item, and the maker or bartender will embellish as they see fit, except in cases like a Gibson where the garnish defines the drink. In that case it’s not uncommon to see multiple suggestions, such as on Old Fashioned which can be garnished with an orange peel, or an orange wedge and cherry, or however you like to adorn your glass.

Common garnishes, such as lemon twist, orange peel, olives, cocktail onions, cherries, etc. are not included in the ingredient list because they are typically on hand behind a bar, or in an enthusiast’s kitchen, but if the garnish requires preparation, it is included last in the list.

- 3 Figs

- 6–8 Basil leaves

How to prepare the garnish is then included in the recipe instructions. If the garnish is something that typically wouldn’t be on hand in a kitchen or behind a bar and might require a shopping trip, it’s included last in the ingredient list with a notation.

- 2 Kafir lime leaves for garnish

Instructions

In our survey, instructions are all over the place, sometimes literally. Some were placed on the page too far from the ingredient list. Some were place close enough, but next to the ingredient list. Some came in 2 columns. We found vertical, one column, after the ingredient list (also a single column) was easiest to use.

Writing style also varies across recipes. Some are very direct and clear, and others are so verbose, with so much information that they are very difficult to use. Short, simple sentences or phrases are best.

The AP guidebook agrees. It further specifies that all instructions should begin with equipment, not ingredient.

- **Yes: **In a saucepan, heat the sugar and the water.

- **No: **Heat the sugar and the water in a saucepan.

Where the tool matters, we follow the advice, as in the above example, but we do find beverage recipes are more conducive to verb first instructions.

- Muddle the mint

- Swizzle with pebble ice

Instructions should contain all the necessary information to perform the step, and nothing more, or less.

- **Yes: **In a saucepan, heat the sugar and the water.

- **No: **In a medium sized saucepan, non-stick or stainless, add the sugar, then add the water, then place the saucepan on the stove and apply heat.

- **No: **Mix the sugar and the water

Some instructions use paragraphs to organize their steps, as in one paragraph might contain a few steps. This works for things like baking a cake, where you often mix the dry ingredients together, then the wet ingredients, then both, but for beverages, that’s rarely the case, so we use one instruction per paragraph, which is often just a short sentence or phrase.

We found the shorter the instruction, the better it can be followed. Beverage recipes often have their own shorthand, and equipment can be personal preference, so we adjusted our rules to specify action and result. Instructional shorthand works for beverages, although some specification of tools is acceptable.

- Stir with ice.

- To a mixing glass, add the ingredients, with ice, and stir.

A food recipe might simply say something like, “saute the onions until translucent.” Drink recipes, for us, are similar to that. To simply say “stir with ice,” or “stir with ice until chilled,” is very similar. It assumes the maker understands how to saute onions, or how to stir. The method can vary. Some practitioners like to stir in one way, with one kind of ice, others like to work differently, and the recipe instructions cannot say exactly how long it will take to stir and achieve proper results. But the instructions can assume that the maker understands what the instruction is communicating. We tried a number of instructions, and settled on a shorthand that communicates, but is very terse.

- Shake with ice and serve up.

- Garnish with a lemon twist.

It’s compact and clean, but, occassionally there are more steps

- In a shaker, muddle the mint

- Add the remaining ingredients, and shake with ice.

Notice how, in some cases, serving instructions are included in an instruction, and in some cases are their own instruction. Up or on the rocks is fairly well understood, but, if there is a specific serving glass, for example, it must be called out in the instruction, and always begin with a verb, such as serve, or top, or garnish, etc.

- Serve up.

- Serve up in a coupe.

- Top with sparkling wine.

- Garnish with a sprig of mint.

In the end, there aren’t really that many instructions required to make a cocktail, even complicated ones. However, there may be ingredients that must be dealt with before the drink is made. Remember that cake? With the dry ingredients first, then the wet, then mix them all together? We don’t do that. If there is an ingredient that is specific to the recipe, or not one of the standard pre-made things (simple syrup, honey syrup, fresh juice, etc.) we add the recipe for that thing before the recipe for the thing it’s in. The Clover Club is one such cocktail that calls for raspberry syrup. When we post a recipe for it, we post the recipe for the raspberry syrup first, then the recipe for the Clover Club. In that way, you could take the syrup recipe and make the syrup for lots of other things you might like to try, without having to parse it from the post’s parent recipe.

Additional information

Far too many of our samples offer way too much additional information in the instructions, making them hard to use. All of this information can be in a recipe description. If there is additional information, which could be notes on ingredients, tips for technique, a bit of history, or some cultural context, it’s best placed in some notes or an essay before the ingredient list. Any post on The Portland Pour follows this format, a title, a picture, an essay, an ingredient list, and instructions.

Servings

Many recipes specify how many servings it will make. This is totally useful information because no one needs to make a big pot of something only to find out it will feed 8, and they’re only cooking for 2. For cocktails, however, we can assume that they are single serving, so we don’t specify servings unless it’s more than one, such as in a recipe for punch, or when it’s not practical to make just one, such as our recipe for Spiced Apple Cider, which is a recipe for 2 servings. In that case, servings are specified immediately preceding the ingredient list.

Time (prep, cook, and total)

Timing on a recipe is crucial if you need to know how long to cook something. Not much of that happens in beverages, but where it does, call out time in the instructions.

- Lower the heat, and simmer for 4 minutes

As for prep times, they can also be super helpful in food recipes, but we find it unnecessary information. The time it takes to mix a drink doesn’t really vary that much, and the steps are pretty standard. If the drink we’re presenting is a project that doesn’t have to be one, such as a recipe that requires and infused vodka, and you have to infuse the vodka yourself, well, that prep time can be a week or more. Best to just mention it in the description, and leave the core recipe strictly about measurement and assembly.

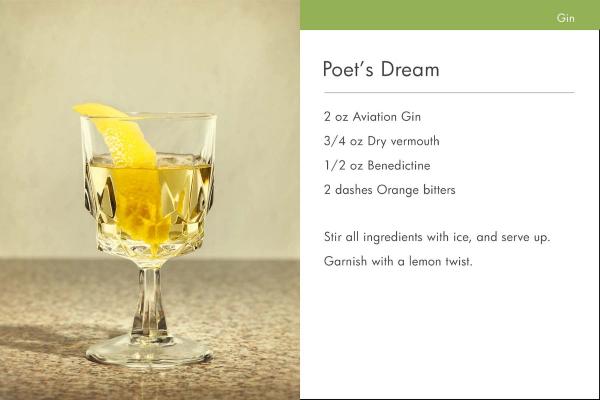

Putting it all together

In the end, we wanted something consistent for our upcoming recipe cards. We feature a picture of the cocktail as we envision it on the left, and the recipe on the right. At the top we add a color band for base spirit, so one can flip through them in a recipe box and see what each recipe is more or less about. On the back, we left a place for notes, in case anyone using the card has some personal preference, or additions, or any comments they’ve added to our information.

Conclusion

Overall, recipes can be very simple or very complex. Beverage recipes, our concern, are usually simple, but can seem complex in many ways. As with all things UX, a little attention to detail, and consistency of presentation goes a long way to making a recipe easy to use. Even if it’s on your phone, sitting across the counter as you measure and pour, it can be easy to use if you think about what it takes to make it useful at a glance.